For 30 Years: A Justice-Centered Mission

The School of Law celebrates the 30th anniversary of its founding and its continued trajectory as a legal education leader.

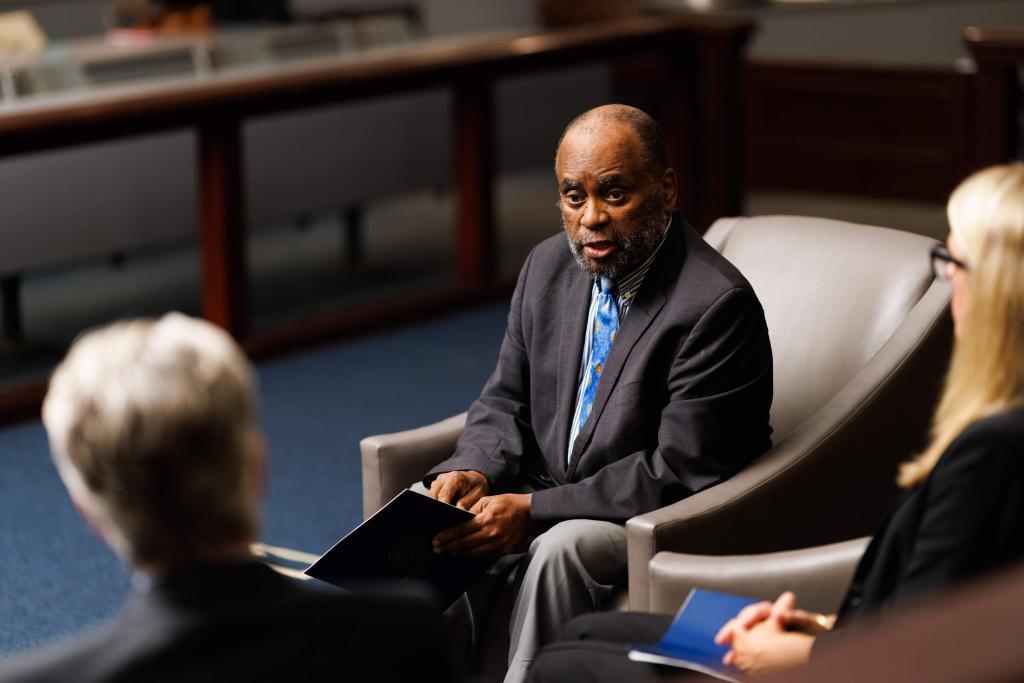

This fall, RWU Law Dean Gregory W. Bowman held a far-ranging conversation with law school leaders to reflect on this milestone year, the school’s history and commitment to advancing social justice in legal education, and a bright future that includes the launch of the Institute for Race and the Law as the next step in RWU Law’s leadership on racial justice legal education. The following pages provide excerpts of his conversation with Associate Director of Pro Bono Programs Suzanne Harrington-Steppen and Director of The Institute for Race and the Law Bernard Freamon.

Gregory Bowman: As the School of Law celebrates our 30th anniversary, I wanted to get your thoughts about where the law school has been and where we are heading. Both of you lead work that sits at the heart of our mission: experiential education with a focus on social justice and our nationally recognized work on racial justice legal education. These two areas really reflect our law school’s history and our future.

Suzy, you have been at RWU Law for 15 years in our Feinstein Center for Pro Bono & Experiential Education. Alan Shawn Feinstein's financial gift – which established our requirement that all law students complete pro bono legal service before graduation – really shaped our law school’s DNA in meaningful ways from the very beginning. How has that gift, and our focus on pro bono experience, made an RWU Law education distinctive and evolved into the launching of our innovative Pro Bono Collaborative?

Suzy Harrington-Steppen:

Mr. Feinstein’s generous gift established the law school’s 20-hour pro bono requirement which later expanded to a 50-hour requirement. This, combined with Associate Dean Andrew Horwitz’s leadership in our experiential education programs and Professor Laurie Barron’s leadership in public interest programming, was foundational in creating the RWU Law brand of legal education excellence – one that challenges students to understand the relationship between law and social inequality, and to integrate the professional responsibility all lawyers have to improve access to justice and the quality of our justice systems.

From there, the School of Law launched the Pro Bono Collaborative (PBC), under the direction of Professor Eliza Vorenberg, where we have created legal services from the ground up, in areas of the law and in communities where there was no free legal service. The PBC, with our incredible alumni network and the generous support of Mark Mandell, literally creates new sources of free legal services and expands existing services – from criminal record expungements to family preparedness planning for immigrants, and most recently our work launching the Eviction Help Desk project, just a few of our dozens of projects. This is a very unique commitment the law school has made to our state and clearly demonstrates to our law students our law school’s values. Nearly 70% of our law students participate in a pro bono experience through the PBC or our Alternative Spring Break program. In doing so, they are provided with scaffolding to think critically about the root causes of poverty and injustice, as well as their professional responsibility to increase access to justice and improve the quality of our justice systems.

Bowman: Bernard, you joined us last year to help lead our newest required course, “Race and the Foundations of American Law,” and are helping to guide our expanding leadership in teaching about law and racial justice. You have led a distinguished career teaching at many prestigious law schools. What drew you to Roger Williams University?

Bernard Freamon: I thought the decision the faculty took in response to the call for curricular change around race was a courageous response and I wanted to be a part of it. Some law schools offer a menu of courses to law students or they'll offer a one-credit course, but very few law schools have taken judgment that there should be a mandatory three-credit course on the relationship between race and the law.

Bowman: It's also striking in the context of our location here in Rhode Island.

Freamon: It's very important from a historical point of view that the law school is located in Bristol, Rhode Island, a commercial center of the slave trade. And so, for this particular law school in this particular location, it is important that our students understand how this legacy impacts us today.

Bowman: I started here in summer 2020, right after the murder of George Floyd, and my very first meeting was with our Black Law Student Association, the student group that advocated for, among other things, establishing a required course on race and law. I know all law schools faced that same moment of national reckoning on matters of race, but RWU’s response went further than most. Suzy, could you share your perspective on our law school’s response and any changes you’ve seen?

Harrington-Steppen: In the years leading up to the summer of 2020, under then-Dean Michael Yelnosky’s leadership, the law school created a strategic plan for diversity and inclusion and changed its mission statement to make clear that the law school is committed to promoting social justice, to teaching about the relationship between law and social inequality, and to creating an inclusive community that welcomes and celebrates people from diverse backgrounds, especially those historically underrepresented in the legal profession.

RWU Law has had a strong commitment to racial justice and to recruiting and building a diverse student body; but our curriculum neither reflected the diversity of our students, nor did it account for the long and complicated history of our legal systems and how these systems have legitimized and maintained racist laws, policies, and structures.

That shifted in June 2020 when our Black Law Student Association presented the administration and faculty with a list of demands, including a mandatory course on race and the law. The faculty unanimously voted to add a required three-credit course this subject. With that vote, and your leadership, our law school initiated a monumental shift in educating and training anti-racist lawyers.

Bowman: I was there for that meeting. I hadn’t even started here yet and it was amazing seeing the RWU community step up in such a meaningful way.

How do you think our “Race and the Foundations of American Law” course prepares our graduates for their careers in all areas of the law?

Harrington-Steppen: If we want our profession and our legal systems to be equitable, every lawyer, regardless of practice area, must be prepared to use their influence and power to improve our legal system and dismantle white supremacy. Our graduates are tomorrow’s judges, law firm partners, general counsels, elected officials, school board members, nonprofit board members, zoning board members, etcetera.

Harrington-Steppen: How we educate our law students matters and the Race and Foundations of American Law course is an important step in the right direction.

Freamon: As Suzy noted, our graduates practice law all over the country in all kinds of important positions. And so their understanding of both legal doctrine and how it is impacted by race is very significant. The course also helps them better understand their own professional identity and to see themselves as lawyers in a new light. Hopefully, this will generate different approaches to client and witness interviews, relationships with judges – all the things that make the legal system work.

Bowman: Whenever I attend law school meetings across the country these days, people are asking not only about our course, but also the Race and the Law scholarship being produced here at RWU and the outstanding work being done outside the classroom to support our students. This year, Bloomberg Law recognized our “Race and Foundations of American Law” class as one of the country's most innovative law school social justice programs. What are the other things RWU has been up to in this space?

Harrington-Steppen: Back in 2017 – before the race and law course – Professor Nicole Dyszlewski asked me a question one afternoon: “Why isn’t there a book to help faculty members incorporate critical perspectives on diversity and equity into their teaching?” From there, the “Integrating Doctrine and Diversity” book series was born. I have been fortunate to co-edit the book series with Nicole and three other colleagues from other institutions. Our first book, geared toward the 1L curriculum, was published in the spring of 2021. Our second book, for faculty teaching upper-level classes, is due out any day. This was Nicole’s simple yet profound idea: let’s get teachers to share what they’re doing around DEI and build support for this work. With the launch of the course and the attention the first book received, Nicole launched a wildly popular speaker series that is now co-sponsored by CUNY Law, Jurist, GW Law, and Berkeley Law.

Bowman: In fact, 90% of US law schools have sent at least one person to Nicole’s “Integrating Doctrine & Diversity” speaker series. As a result of this work, the American Association of Law Schools invited us to present a half-day seminar at their annual meeting in San Diego this year on integrating racial issues into both the classroom and the courtroom. And next spring, RWU will be hosting law school diversity and inclusion professionals from across the country for their annual conference. There really is something palpable going on here.

Harrington-Steppen: While all of this attention is fantastic, we are still very much a work in progress. This work doesn’t end, nor is there a clear right or wrong way to do the work, but we are doing it.

Bowman: Which leads me to my final topic and the exciting next chapter of our social justice work. Bernard, this year you are leading the launch of our new Institute for Race and the Law and the fundraising to support the Institute and its work. How will it be both a catalyst for change and a place for change?

Freamon: One of our goals with the Institute is to establish a Teaching Fellowship Program, where lawyers at the beginning of their careers come to Roger Williams and teach in our “Race and the Foundations of American Law” course and help us broaden our curricular offerings. We hope that after their fellowships they join faculties elsewhere and focus their academic research, teaching, and practical work on issues of race and the law. The Institute will also encourage practical work that makes a difference in the community, while also offering programming that is relevant to both college students and secondary-school students. Engaging with other universities and secondary educational schools will make a difference in changing the society.

Freamon: A university is really not worth its salt if it doesn't do things that help to bring about change in society.

Bowman: Let’s look forward to the next 30 years. How do you think we will evolve?

Freamon: This is the only law school in Rhode Island and 30 years from now, I would still like that to be the case. I hope we will play a central role in how Rhode Island makes its legal policy judgments, because there is a lot of work to do in terms of social justice, and I hope that Roger Williams University would be at the center of that work.

Harrington-Steppen: I hope when we look back, we see that the “Foundations of Race and American Law” class was a catalyst. RWU Law is a place where we should be experimenting and making law school actually look and feel different. I want the law school to take this momentum and run.

Bowman: That's a great place to close and to thank you both. We all really appreciate what you do and the fact that you're helping us lead the way.